Ashes

By Riley Bartlett

When I boarded the bus at the airport, I didn’t know about the Marshall Fire whipping across brush and grass, dry from warm weather and too little rain. When I saw smoke, I tried to convince myself the falling ash was rain as the windows rattled.

11:45am: “Wildfires were reported in Boulder County. It’s not clear how the fires started” —Denver7.

The girl next to me said, “Is no one going to talk about that?”

11:55am: Under dark sky, wind howled as we turned a corner. Soot and ash flew. McCaslin Station scrawled across the monitor.

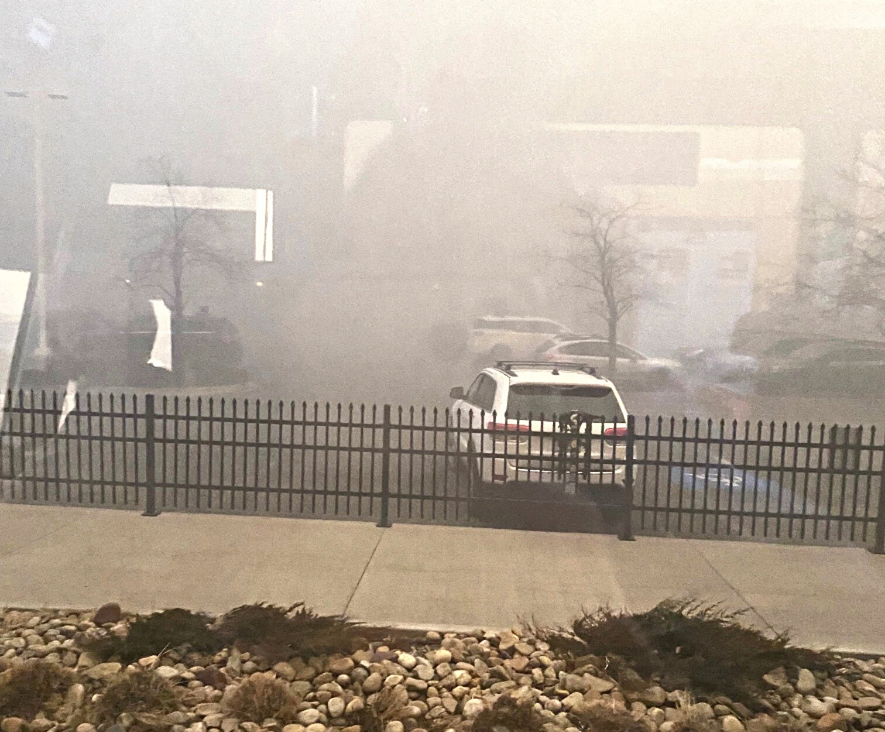

11:57am: I took a picture and sent it to my sister, a few friends, and to my partner, Rain. I received messages back: “What’s happening?” “Is that smoke?”

12:00pm: We pulled into McCaslin and the driver began unloading the suitcases. Through the front window, cars vanished.

Off the bus, I breathed in and coughed. Wind hunched me over as hair and ash whipped around me. I approached the driver and asked if I could get off at Table Mesa.

“I think we’re stuck here,” he said.

“I have no way to leave.”

“I’ll let you back on.” He put my suitcase back under the bus.

I thanked him, got back on, and took an empty seat at the front. As I coughed into my mask, I felt soot, so I switched it out. Inside, it was black. Coughed. Coughed again. Grit in my hair. Black on my chest, my stomach. Eyes stung.

I texted Rain I was getting off at Table Mesa, but we were stuck.

“I can pick you up and you can stay the night.”

We hadn’t been dating long and I hadn’t spent the night, hadn’t even been to their place so I hesitated, but said yes.

12:05pm: The woman behind me approached the driver, “We shouldn’t be here. It’s not healthy.”

Her British accent made me think of the UK, the temperate climate of growing up in New England.

In high school, I attended an arts program in Vermont. One weekend, we camped in the forest. The city kids were afraid of bears, of getting frostbite in 60-degree weather, and refused to pee. Then, there were the California kids, who were afraid of sparks flying from wet pine, hitting dead, damp leaves. One girl asked, “Aren’t you worried those will catch fire?”

“We don’t need to worry about fires on the East Coast,” I said.

12:10pm: The driver rubbed his face with a paper towel. “Look,” I said and showed my mask to the people behind me. They sat up, craned their necks. Wanting a closer look, one man demanded I pass it to him.

The woman with the British accent said, “This is unsafe. We need to go.”

The driver replied, “I can’t. The way out is blocked.” He gestured to the police cars, their flashing lights faint, “I would have to drive into oncoming traffic.”

Outside, a man braced himself against the shelter, back to the wind, hood over his face.

I was texting Rain when the woman behind me screamed, “I see flames!”

Orange, fifty feet away, grew into a bonfire. I thought, “am I going to die?” Disbelief. No, that couldn’t happen.

No one believed my friend Jules would die. Song and dance burst out of her. Breathing through movement, she swayed and turned and reached. The day of Jules’s first seizure, I was laid up in bed. Light was white and grey. If I closed my eyes, my head pulsed. Eyes open, my head split. A month before her eighteenth birthday, Jules was diagnosed with brain cancer.

12:15pm: The woman with the accent asked, “Should we run?”

Feet pounding concrete to outrun errant sparks. Inhaling slithering ash. Becoming a ragdoll in the wind.

“Getting off this bus is the worst thing we could do,” I said.

Flames grew. Smoke thickened. A plastic bag flew across the street.

Jules’s mom described the cancer as a tornado that ripped everything away. A few months into treatment, Jules came to dance, eyes ashen, skin sunken. Every time she spoke, her eyes looked elsewhere. Our teacher counted her in and she missed the steps, was off time. Our teacher choreographed a lift for Jules, but she leaned forward and caught herself. Silence. I said, “We’ve got you.” We caught her hands. Lifted her chest. My arm wrapped around her thighs. In the air, she felt as light and delicate as bird bones.

The last time I saw Jules, she came to rehearsal but didn’t remember a thing. I remember her running off in tears. I remember her eating chips and then rice and beans at dinner. I didn’t know I wouldn’t see her again.

On the bus, I received a text from my neighbor, “Remain calm.”

12:30pm: Blue and red lights and sirens. A cop pulled up and the driver let him on. “We’re going to clear the on-ramp and we’ll signal you to drive out.”

No one cheered, not yet.

When we pulled out, there was a collective breath, but then we saw the bushes in the parking lot smoldering. Then, we turned a corner and the sky was blue, the sun bright, the smoke making a wall behind us.

12:50pm: At Table Mesa Station, I tipped the driver as he unloaded my suitcase. Trembling, I thought I was finally safe. All I needed was a ride. Lyft and Uber wouldn’t load. Calls went to voicemail. At the bus shelter, I waited as wind tore through my coat, bit my neck, and made me shiver.

1:04pm: “Smoke is making it hard to see. First responders are moving around the traffic.”

—Denver7

A child and his mother played with toy cars on the benches. A car came and picked them up and I waited. Another couple got into a car and I waited. Rain texted me, said they could pick me up, but I said traffic was awful so I’d take the bus.

1:20pm: The DASH arrived and I was the only one who got on. As the bus pulled away, I braced my suitcase against a seat and refreshed the news.

We drove bumper to bumper. The driver commented on the traffic and I said people must be evacuating or trying to get home. He was grateful his family was safe and said this was an example of needing to surrender to God.

Fearing judgment, I said, “I’m spiritual, but I don’t go to church.” It was a half-truth. I was afraid to say I am queer and non-binary, to say church often wasn’t the safest place.

But I gave him updates on the fire and he talked about how if we believe in Jesus, we are saved. I didn’t tell him I don’t believe in God, in heaven, in hell, because people need to take comfort in what they can.

I’d like to believe a power takes care of us, but when I taught high school, several students died, suddenly, tragically. My colleague posted a picture of herself in a graveyard with the caption, “Going to my student’s funerals never gets any easier.” I thought about them. The one whose brother found him with a needle in his arm. The one who broke up a fight, but was shot, lost her lung, and when she died, she left behind her two-year-old son. I thought about my best student, always bent over her papers, pencil moving while other students played games, but she was shot walking down the street in Denver.

1:58pm: “If you see fire don’t wait for an evacuation alert. People in the southwest Boulder area should drive north or east” —Denver7.

Haze crawled toward the road. I told the driver we needed to go through the evacuation zone and over the roar of the bus, the honking of cars, the bumps in the road, he told me about Matthew, Job, Joseph and his dreams. It made sense how he clung to religion and I let his words wash over me.

4:00pm: “Photos and videos confirm homes are going up in flames” —Denver7.

4:30pm: The driver let me off and up my street, I saw cars in their spots and feeling a little calmer, finally, I walked through my door.

Reeking of smoke, my clothes laid on the tile. In the shower, ash ran from my hair and body, turning the water black before swirling into the drain.

After my shower, I texted Rain, “I want to stay at my place.” Already tired, I was too nervous to navigate the question of where I would sleep at their place.

“If you change your mind, let me know. Be safe.”

5:17pm: “Thursday has been a harrowing day. Tens of thousands of people have been evacuated and hundreds of structures, both homes and businesses, have been lost” —Sheriff

Newscasters reported fire jumping from home to home, shingles falling, windows bursting, siding being stripped away until only support beams were left, then they burned too.

A few months ago, I saw a woman waving her arms on the side of the highway. I switched lanes, slowed down and saw another woman, pressing down against a body in a ditch. This was before the cops blocked off the scene so no one would see the car crumpled like a tin can. All that metal, caved, dented, beaten. Cars of witnesses lined the road and a woman jogged towards the ditch. I would have stopped if I could have helped, but there were already too many people doing nothing but staring. There’s this human need to help, but also to stop, to stare, to freeze.

6:35pm: When I found out the fire could be seen from a nearby street, I texted Rain I was driving over. Looking for anything I should bring, I rushed through my house. In my suitcase, I had the essentials already. I looked at my books; the signed copies couldn’t be replaced, but I didn’t take them. I went through my closets, running my hands past my shirts and dresses. I shoved a small stuffed animal into my backpack and got into my car.

7:00pm: At Rain’s, I was offered a shower after admitting to still smelling like smoke. Between my bones, my body fluttered.

I told Rain I was tired and they said, “You can sleep on the couch, on an air mattress, or in bed with me.”

I was glad they asked, glad I got to choose. Leaning in, I said, “I’ll sleep with you.”

The day before Jules’s first seizure, her mother shot pictures of her kneeling under a pine tree. After that day, appointments, radiation, surgery, consumed them. Instead of attending graduation and going to college, Jules listened to the whir of a feeding tube while her mother searched for hope in clinical trials. I found out she died when her mother posted a picture of Jules clutching drooping roses, their petals falling and scattering over her bed.

The day before the Marshall fire, families sat at tables together and the next their homes burned. On New Year’s Eve, the snow came in a silent shroud, blanketing the foundations of homes that burned, and reduced the remaining fires to smolders. On New Year’s Day, I returned home, but many others drove to rummage through the wreckage. One man brushed soot off a whole plate, undamaged, unbroken.

All I can do is remember. I cannot cling to religion, cannot be saved by it. I cannot find solace in a thing that often creates hate for who I am and love, but I find faith in stories. I remember Jules and my students who died too young. I remember the man who died in a ditch on the side of the road. I remember the pain of all those homes burning. I have faith in Rain’s arms around me, my head against their chest, their nose in my smoky hair, our hands intertwined as I tremble.

Riley Bartlett is a nonbinary dancer and writer living in Colorado. They received their MFA in Creative Writing in 2019 from The University of Colorado Boulder and is now a professor at the University. Their writing has been featured in several dance performances in the Denver Metro area. "Ashes" is their first publication.